5 August 2021 | OPINION

In 2014, the people of Scotland went to the polls and cast their votes on whether to remain a member of the UK – the single greatest economic and political union in history – or leave it for the uncertainty of becoming an independent state. For proud unionists like myself, the result – 55-45% in favour of remaining – was a source of great happiness, but the years that have followed have been increasingly frustrating due to the never-ending cries for another referendum from the SNP.

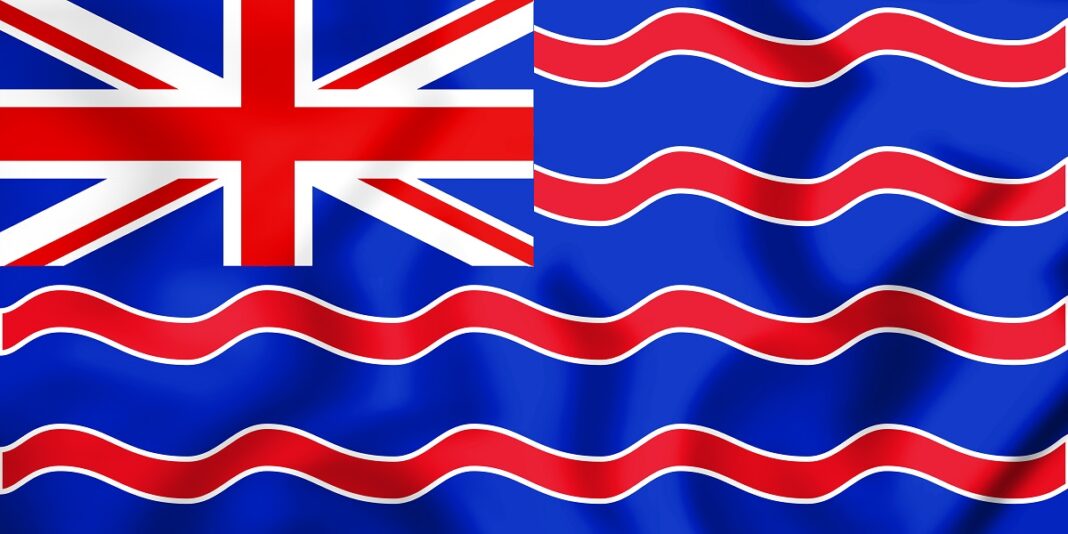

Yet whilst the SNP continue to try and push for a second attempt to break up the union, the people of the British Overseas Territories (BOTs) continue to be proud of being represented by the British state. We in the UK, however, continue to let them down by not providing them with the representation that they deserve on the green benches in the Commons.

Of course, there is an obvious caveat whenever a discussion of this sort comes up: the wildly different nature of the BOTs in question. There is no denying this. They vary massively in terms of GDP per capita, geographical size and a whole range of other factors. Yet, for the purpose of parliamentary representation, the single biggest issue is population.

The Pitcairn Islands, the smallest permanently inhabited BOT, has a total population of less than 100, whilst the largest, the Cayman Islands, has over 65,000. So, how do you determine where the cut-off point should be? In truth, I believe that the UK Government has actually already given us the answer to this quandary and reconfirmed it in the past few months.

Years ago, when drawing up the boundaries of parliamentary constituencies in the UK, it was determined that certain seats would be classified as ‘protected’, meaning that they could fall outside of the normally acceptable population range for constituencies. This was often done for island seats, such as Orkney and Shetland and the Isle of Wight. In the recent Boundary Review, it was determined that ‘Na h-Eileanan an Iar’, the seat which covers the Outer Hebrides, should continue to have a Member of Parliament despite having an electorate of only 20,000, far below the 69,000 normal minimum threshold. If we take this as our benchmark, then five BOTs have a greater population, and so in theory have a right to democratic representation in the House of Commons.

Why does this matter? Because the people of the BOTs, whilst largely self-governing, rely on the UK Government to address issues such as securing and receiving Covid-19 vaccines, as well as protection and representation on the global stage. Yet as long as they remain unrepresented in the Houses of Parliament, they do not have champions for their interests. This needs to change, and the aforementioned Boundary Commission presents the perfect opportunity.

For giving the BOTs seats in the Commons is not an impossible feat. The British constitution is famously flexible, and the change would only require a relatively small alteration to current laws.

The Boundary Commission is currently drawing up the new seats following the passing of the Parliamentary Constituencies Act 2020. To guarantee BOT representation, all that would be required is a slimmed-down version of this Bill, explicitly increasing the number of MPs by five and adding in newly protected seats to cover the largest BOTs.

This straightforward alteration would give a voice to over 200,000 people represented by the British Government but unable to vote for it, ensuring that the people of the BOTs can have their say on the issues that affect them. It would bring the UK in line with other countries with overseas territories, including France and the Netherlands. It would help to address a democratic deficit. In short, it is hard to see a downside to looking into this proposal.