1 JULY 2024 | OPINION

Austerity, austerity, and austerity: you’ve heard it before, haven’t you? Who hasn’t – and this is the point. But it’s a lie – 14 years of Conservative government have achieved not less spending, but more.

The public will face a choice in the coming days. Labour has committed to greater fiscal restraint than most other parties in its Manifesto, but opposition is not governance. It may find itself under far greater pressure once in office to dip into the public purse than it foresaw.

The notion that the Conservatives cruelly cut public spending to the detriment of public services is not just a solid trope of political discourse, but is deeply ingrained in the British collective consciousness. How has this come to be?

Ostensibly, low public spending is presented by figures on the left as the cause of national woes. Injecting more money into public services – especially on the sacred cow otherwise known as the NHS – has been portrayed as an obvious ameliorating elixir.

Some Conservative politicians, equally, are also often willing to ‘own’ austerity. It rationalises perceived poor public services as a trade-off for making the fabled hard choices, in contrast with those in Labour who left the country with ‘no money’. They are keen to emphasise a cautious disposition when it comes to the economy.

Simplistic, stale, lazy: it obscures a far more complex reality beneath the surface. Austerity did not cut public spending. In fact, the Conservatives increased it twice.

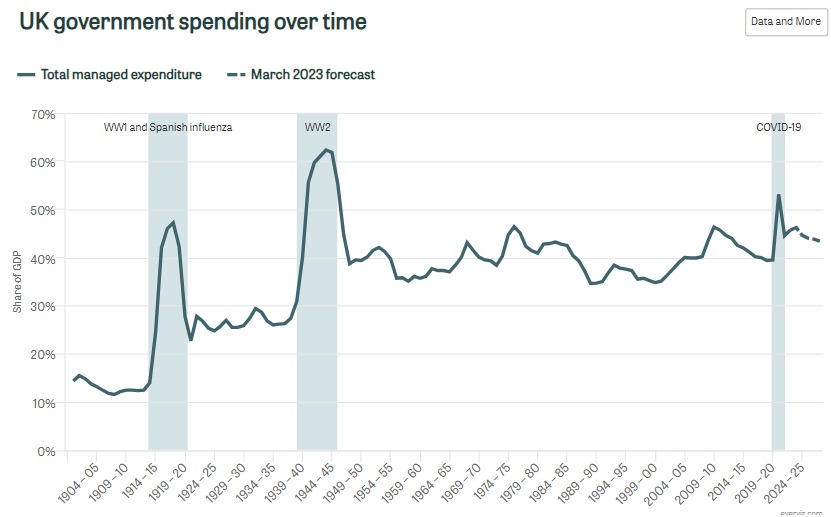

Public spending as a share of GDP has followed a certain long-term trajectory since the beginning of the 21st century: upwards. On a basic level, spending can be broken down into three distinct periods, punctuated by crises. The first period was under a Labour government before 2007. The second period was under a Conservative government from 2010 to 2019.

The third period, which is ongoing, is under a Conservative government since 2022. The 2007-2008 financial crisis and the Covid-19 pandemic were the two punctuating crises that led to extraordinary increases in public spending as a proportion of GDP.

The first period, under a Labour government, was one of an increase in public spending, reaching 40.2 per cent as a share of GDP in 2007-08, before exploding due to the financial crisis. Perhaps unexpectedly, though, the second period under a Conservative government from 2010 did not reduce public spending below the level of Labour’s.

By 2019-20, the figure had only fallen to 39.5 per cent, only marginally below the pre-financial crisis level and considerably above the level of spending undertaken by Labour in the early 2000s, which stood at 35.1 per cent in 2000-2001.

So much for austerity.

What this shows is that much-maligned austerity did not even make a long-term impact on public spending. Austerity only involved reducing spending to virtually the same level, if not more, than under Gordon Brown’s Treasury. The Conservatives effectively implemented a long-term increase in spending following the financial crisis, an increase compared to the level under New Labour. So why did people think this was austerity?

Indeed, the public spending delusion centres around the healthcare sector. Contrary to some political rhetoric, Cameron and Osborne did not cut, but rather protected, spending on the NHS. Real-terms spending on health increased by 1.1 per cent under the Coalition Government. The same is now happening again. We are living through the third period – the post-pandemic one. The pandemic, after the financial crisis, was the second extraordinary spending splurge of the 21st century.

In 2020-21, total managed expenditure was 53.1 per cent of GDP, a level not seen since the Second World War. A decrease from this level was necessary and inevitable.

So much for austerity.

Jeremy Hunt’s Autumn Statement in 2022 was portrayed as cuts-laden and described as a ‘return to austerity’ by Nicola Sturgeon, the then Scottish First Minister. Indeed, both the IFS and the Resolution Foundation have highlighted departmental budget cuts scheduled in the next parliament.

But what are these cuts? What is this cursed ‘return to austerity’? Under current plans, public spending will fall to 43.4 per cent of GDP in 2027-28. Far from cutting spending, Hunt actually introduced another long-term increase. Spending at this level is higher than after the first austerity period, higher than spending before the financial crisis, and higher than spending by the Blair government in the early 2000s.

In fact, only three times since the spending of the Second World War has it been this high: the pandemic, the financial crisis, and in the mid-1970s under Labour. This is a victory for advocates of a larger state.

So much for austerity.

Far from delivering the kind of harsh austerity spoken of, they effectively delivered two consecutive increases in public spending when compared to the level under Labour. An increase following the first austerity period and an increase following post-pandemic cuts.

Fiscal conservatism would have involved identifying the financial crisis and the pandemic as a trap – one that can only lead to a larger state, which ought to be avoided. True fiscal conservatives would have recognised that these existed as pressures to inexorably drive up public spending on a long-term basis.

Fiscal conservativism would have involved not just cutting spending, but cutting it back to the pre-crisis level. This never happened – the Conservatives fell for that trap.

So much for austerity.

But this also exposes the folly of economically interventionist solutions to current woes. Simply increasing departmental spending is not the panacea. Outcomes of public services, such as the NHS, will not improve without addressing deep-seated structural defects.

Record levels of money are being injected into the NHS; soon, healthcare will account for 44 per cent of all day-to-day spending. Simultaneously, public dissatisfaction for the NHS sits at a record high.

According to the British Social Attitudes survey, 52 per cent of people are ‘very’ or ‘quite’ dissatisfied with the NHS, up from 25 per cent in 2019 and 18 per cent in 2010. People clearly feel as though the NHS is broken, yet more money is being spent on it than ever before.

So much for austerity.

The mirage and illusion of austerity has yielded a convenient – yet flawed – diagnosis for poor public service performance. The impression that public spending is too low easily offers a false rationalisation for the shortcomings of every part of the public sector.

This impression is riddled with fallacy, because it ignores any responsibility held by those accountable for budgets as to how they spend them.

The issue for the Conservative Party is that political capital has been expended on the impression of austerity without the delivery of a seminal conservative outcome – an outcome that would take the form of a decreased in public spending.

The notion that austerity actually cut public spending has been ‘baked into’ the British collective consciousness – the Conservatives have irrefutably lost millions of votes over the years, because people attribute poor public services to supposedly low public spending levels.

Yet, they will leave office with it running at a higher level than under New Labour. Too much rhetoric, too little delivery. The same can be said of other matters ‘baked into’ the public consciousness, such as Partygate.

Everyone likes to talk about how the tax burden is the highest in 70 years. If we had more honesty, if we acknowledged that public spending is high, and if we recognised the degree of trade-off between high spending and low taxation, then perhaps we might be better able to understand why the tax burden is so high.

We need to re-write the narrative on public spending. High spending is the reality of the past 14 years. High spending does not always deliver better public services. High spending is what we have now. Now is the winter of our public spending hangover.

Public spending is a matter riddled with public delusion. We have been sleep-walking down the garden path on this score for far too long. When will we sleepers wake?

So much for austerity. May its mourners weep.