1 APRIL 2022 | OPINION

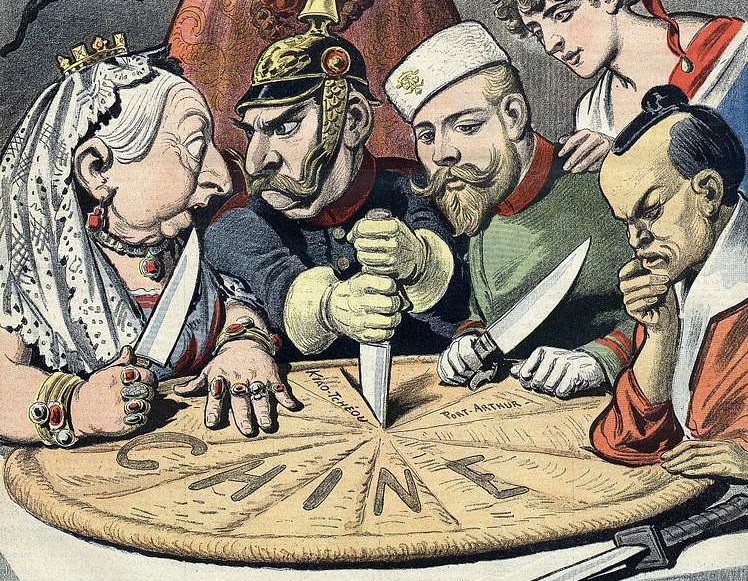

Teaching about the British Empire in schools has become a bit of a thorny issue. It has become politicised by every side across the political spectrum, but in recent years this has taken a rather more sinister turn – it is being weaponised in some quarters to delegitimise all of Western civilisation.

Do you teach students about the Empire at all? What angle do you approach the subject with? Did colonialism have any positive elements? These questions have formed part of the ongoing ‘culture wars’. The topic of colonialism cuts right to the heart of these wars, as it relates to the essence of the notion of ‘Western exceptionalism’ and the modern world.

The latest Cabinet Minister to wade into the debate was the Equalities Minister, Kemi Badenoch. In an interview with Times Radio recently, she argued: “History isn’t about trying to enforce a particular narrative. It’s about telling the truth about things that happened. There were terrible things that happened during the Empire. There were other good things that happened. When I learned about it in Nigeria, we got a very nuanced picture. But there wasn’t any sort of attempt to describe the Empire as having just oppressed them.”

Having spent a significant amount of time within the Social Sciences departments at university, I have been able to experience the way the issue is taught and seen the context within which colonialism is discussed.

To some extent, Ms Badenoch is correct. The teaching of colonialism across universities is entirely negative. Colonialism and empire are dirty words. Any association with either colonialism or empire is treated with contempt. In this sense, then, there is some truth behind what she says. To avoid being taken out of context, it must be stated that of course unspeakable actions certainly did occur under a colonial banner. These deserve to be addressed appropriately.

Nevertheless, that does not neglect the notion that there were some positive outcomes. But what Ms Badenoch is observing are the symptoms of the disease and not the actual root causes. The controversy surrounding the bias in the teaching of colonialism emerge from ideological positions that have been plaguing academic institutions for a very long time. These theories are being further utilised to construct an overarching anti-Western narrative, one facet of which is the side-lining of the different contributions of the British Empire.

To show why the perceived positive effects of the British Empire are being ignored, it is necessary to firstly note the perceived positive impacts.

Broadly speaking, the positive contributions of the British Empire can be broken down into two main camps. The first was the spread of Western values across the world, which took the form of democracy, the basic structure of freedom and rationality as it relates to the scientific method as a way to determine progress. These traits continue to be found littered across the former Empire.

The second contribution was the introduction of capitalism and the integration of different people into the world economy. This was also linked to the pursuit of material prosperity, industrialism and raising the quality of life.

There are many sub-categories that can be included under these headings, but generally they can be seen to originate from either Western values in general or capitalism in particular.

So why, then, do these positives not get discussed?

There are certain assumptions underpinning these perceived positive impacts of the Empire that are picked apart by the prevailing ideologies consuming university departments.

The first assumption relates to the post-modern critique of the West. Post-modernism is by far and away the most significant theory taking hold in Social Sciences departments. This ideology questions the very notion that Western ideals are valuable and that they should be advocated for at all.

Michel Foucault, the father of post-modern social thought, argues that the notion of Western rationality and reason is merely a by-product of power relations conducted and influenced by the powerful within society. The ensuing argument is that the knowledge held by Western civilisation is neither objectively good nor correct, but rather originating from set biases.

This train of thought has been adapted to the context of colonialism and the representation of the history of the Empire. It holds that it is only possible to discuss the positive impact of Western values if you believe in the objective superiority of Western beliefs, but that in a world where Western values are seen as merely a manifestation of power relations, those cannot be seen as superior to any other value system and, therefore, the argument that there could have been any virtue in spreading Western values, according to post-modernists, is non-existent.

Furthermore, the argument that the dissemination of capitalism and the emergence of industrialisation across the Empire was a positive stage of development falls foul of another ideology that has taken hold in Social Sciences departments. The Marxist critique of capitalism and industrialisation is infamous, as too is the grip that Marxism has on university professors. It is unsurprising, therefore, that the relative successes of capitalism across the Empire remain in the dark.

Both Marxism and post-modernism are being harnessed with the intention to depict the West as a civilisational demagogue, with the ultimate goal being the disintegration of the Western world. These are the hallmarks of the revolutionary Left movement. To “reimagine” society (a word that is frequently used in the Social Sciences to replace “revolution”) without inequalities or power relations, one must destroy the existing structures so that a new one may subsume them. This is not a push to enhance society, but rather to replace it.

Ms Badenoch, consequently, is only perceiving the symptoms of the disease when she discusses the legacy of colonialism. While she is correct that the discussion of colonialism and the Empire is one-sided, she has perhaps not considered why the discussion is being framed though one particular lens.

Discussions around the subject are being conducted in the context of post-modernism and Marxism, which are the dominant ideologies on university campuses. These theories are being used for the broader aim of social revolution through the undermining of the existing system. It is, therefore, unsurprising that contrasting views of the Empire are not elaborated upon – that would not suit the agenda of those who wish to deny their very existence.

It might be tempting, as a politician, to confront the issue you are faced with on its own turf – but that is exactly where they want you. It may be better, in cases like this, to pay rather more attention to why they want you there.

The truth should be told in its entirety, not your dodgy fake version of it you little snowflake rat. How do you people have the nerve to call yourself journalists.