10 May 2021 | OPINION

Within my very first days of moving from Hungary to the UK, I felt ambushed by Marxism.

While queueing to get into the fresher’s fair as a first-year student at UCL, I noticed the stall of the Marxist Society. The students behind the table were wearing old-fashioned newsboy hats with little hammers and sickles and Lenin badges.

Coming from a post-Communist country, this scene rather shocked me. It also reminded me of an old story we tell in Central Europe of a Czech professor who returned to Prague in the 1970s after two years in the Netherlands because – as he said – ‘there were way too many Communists over there. At least in Prague, I won’t have to meet any’. Ever since the freshers’ fair, the spectre of Communism keeps haunting me in my studies – which raises the question of how these ‘ghosts’ can be more ‘alive’ in British politics and higher education then in post-Communist Central Europe? And what can we do about that?

One of the possible explanations for the current popularity of Marxism is the very limited knowledge most of the UK has about Communism. When I was tutoring first year students at the School of Slavonic and East European Studies of UCL, the level of ignorance I encountered about Eastern Bloc history was unexpected and bewildering, considering they had chosen it as their area of specialisation. The majority of them claimed to have never heard of Brezhnev, nor Khrushchev, nor could they comprehensively explain what a ‘planned economy’ stands for.

If even these basics are generally not known, it is unsurprising that students often do not recognise that many ideologies popular among them are predicated upon Marxist thought, or the danger this poses. Over 30 years ago, the New York Times warned about the mainstreaming of Marxism in higher education. The situation has worsened since then. Ideas which are fundamentally Marxist in nature – like Post-modernism and Wokism – now play a prominent role in university syllabuses. Further, because of the lack of understanding of the impact of these ideologies in practice, they are supported passionately by many students.

Part of this ignorance is due to how little attention is dedicated by the British Government to preserving the memory of the Cold War era. During World War II and during the Cold War both Nazism and Communism were conceptualised as ‘evil’ but their treatment since then has differed, impacting on the ways they are understood. While there is a universal agreement in the UK that the remembrance of the Holocaust and World War II is necessary, little is done to preserve the memory of the suffering caused by Communism. As a result, the trauma of Communism does not play an integrated part in the collective memory of Western Europe and Britain.

Nazism became equated with political evil especially after the horrors it committed were exposed after the end of the war. This occurred through the consolidation of a collective memory through education and annual commemorations. However, a strong association between a political ‘evil’ and Marxism never became firmly established in the minds of the British public after the collapse of the USSR. This is because the two ideologies are treated differently in many spaces including education and politics.

Even if Communism is not condoned at a governmental level, there is less effort put into attacking it and mourning the crimes of Communist regimes than there is for attacking the Nazi regimes. Hence, in the absence of the stigmas which should exist, Communist symbols can be freely used in public places, and Marxist ideas can be taught at universities. As a result, the ideology can continue to prevail.

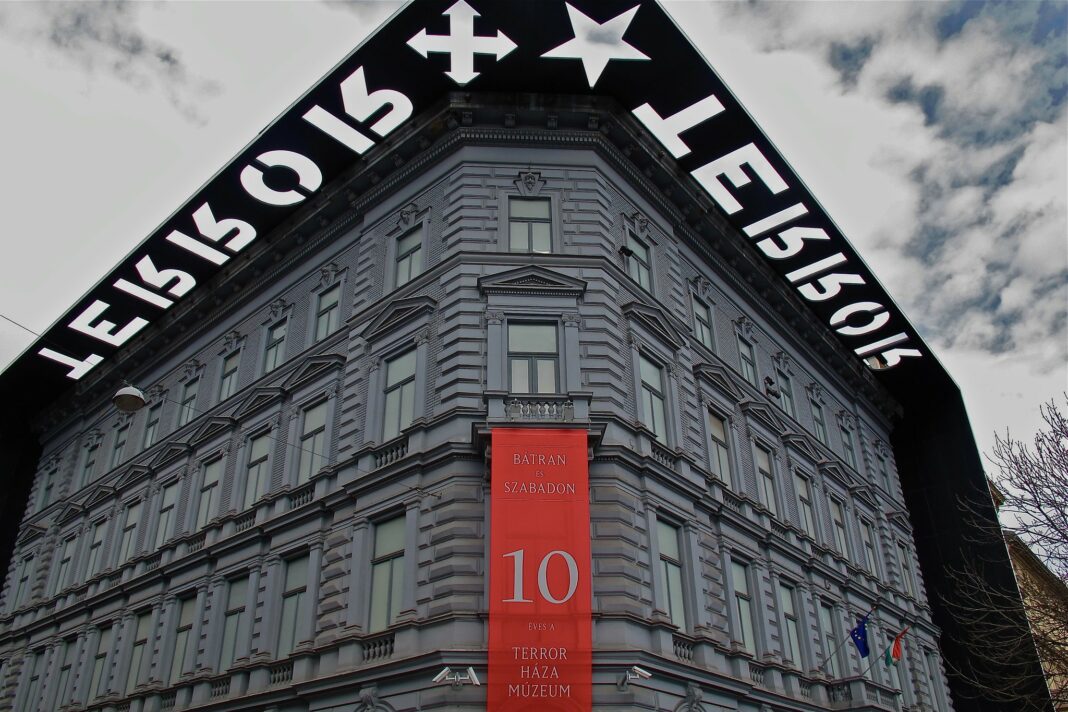

One way to reverse Marxist sentiments is to remind the British public of all the human suffering caused by Communism. This can be executed through initiatives modelled on those for Holocaust education. As politicians visit Holocaust memorial sites, they should also be encouraged to pay their respects at the sites of Communist terror. One such site is Katyn, where there were mass executions of nearly 22,000 Polish military officers and intelligentsia. As well as Holocaust survivors speaking on campus to remind British students of the malevolence of the radical right, the testimonies of former gulag inmates and Soviet political prisoners should be heard to remind British students of the terror of the radical left.

The British public takes pride in its involvement in the defeat of Nazism and is annually reminded of it by commemorations of the sacrifices Britain made to achieve this. So too, the British public should be reminded of its struggle against Communist extremism and commemorate its efforts to combat it, such as military decisions and espionage during the Cold War and defending West Berlin. 1989 should be seen as a year of freedom from oppression, just as 1945 is.

In the last 3 years, I have heard multiple Conservative MPs expressing concerns about Marxism and Wokism at universities. A viable antidote to such sentiments is repeatedly revealing the malevolence of the radical left. British politicians should take the first symbolic step by making pilgrimages to the sites of Communist terror. This should be followed by education programs and commemorations organised by the State.

To dismantle the romanticisation of Marxism and the views of the woke left, the British population needs to collectively be repeatedly shown the immense suffering caused by Communism. The State has the power to make this happen most effectively.

Lili Naómi Zemplényi is a Policy Fellow of The Pinsker Centre, a campus-based think tank which facilitates discussion on global affairs and free speech. The views in this article are the author’s own.

Agreed that Marxism and neo-Marxism have taken a hold in the UK, spreading from academia this ideology has even infected corporations.

However, the author suggests that “dismantle the romanticisation of Marxism ….. The State has the power to make this happen most effectively”, that one fears is a Marxist approach.

It is not the State’s job to dismantle ideologies, but it is within the State’s remit to stop funding them. Defunding the BBC would be a good place to start.

The government should replace woke heads of taxpayer funded institutions and cut funding as many have been captured by the upper-middle class elites who are enthralled by communism and its offshoots. University teaches “being against”, hence any system, except that of the West is considered a “progressive” and attractive cause.

If state institutions have been captured, then it takes state-level action to free them. Otherwise the state is complicit in their capture.

The EU has been poisoned with Marxism too. Look no further than the VP of the EU Commission, Maros Sefkovic, who studied in Moscow then joined the Communist Party in 1989 just as Communism fell. Effortlessly he drifted into the EU, a home from home.

Seems awful authoritarian to tell the people what they’re allowed to think.

I suggest that two things lie behind the failure in Britain to recognize that communism was just as bad as fascism.

1. It was not possible to ignore Nazi Germany when they were bombing Britain. It was possible to ignore the Soviet Union.

2. The messages of communism – equality, a decent standard of living for all, and so on – sound warm and fluffy (unlike the messages of fascism). Then people can fall into the easy optimism of “It could work well, given the right circumstances”. It is not just that people do not take seriously enough its horrendous record of mass murder and mass starvation. They also do not think about reasons why it can never be expected to work well, even in ideal circumstances – for example the reasons set out in Hayek, The Road to Serfdom, chapter 10: “Why the Worst Get on Top”.

I think it’s more subtle than that. Remember Churchill saying “if Hitler invaded hell, I’d put in a good word for the devil”? Because Soviet Russia was our ally in WWII, criticism of the regime was suppressed. Unfortunately the habit never really died as it was in tune with the idealism of those who grew to adulthood in the 1930s. It’s very difficult to shake off an entire mindset, especially if it’s shared by many of those around you, and its critics (those who spoke out against communism) are tarnished by association with Nazism.

Excellent article, thank you. It is easy for us to be complacent about our home-grown Marxism supporters, so it is important to be reminded of how bad it looks to people from countries that have experienced the horror of Marxism in practice.

This is indeed very worrying. James Bartholomew’s proposed Museum of Communist Terror https://www.museumofcommunistterror.com/ is an excellent initiative that is worthy of substantial public funding, so that it could provide educational services for schools etc.

Never heard of Khrushchev or Brezhnev? In part this ignorance is the fault of the O-Level and A-Level history curricula. I recall Ruth Henig, formerly of Lancaster University and now a Baroness, telling me she’d encounter enthusiastic young smarties who’d shone quite brilliantly in A-Level history but had never heard of the Berlin Airlift or the Korean War.

Putting this on the First-year reading list for politics & history students would be a good first step –

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Black_Book_of_Communism

On a lighter note, on Youtube there is an animated cartoon version (a clever mashup) of the entire Manifesto of the Communist party. Recommended viewing!

In the 70’s I was doing an HND in Mech. Eng. and there had to be two hours of Social Studies so that we were “more rounded”

One of the discussion classes was about WW2 and the lecturer was a young woman, whose

main point was that the Soviet Union saved Europe and UK USA and allies had a bit part.

I pointed out that she had skipped a few points like the Soviet invasion of Poland on 17th Sept 1939, and murdering Polish POW and others in the Katyn forest. She broke down and cried and I was summonsed by the v. principal. They wanted me to apologize, I wouldn’t, but it petered out, she did stay around the college for a time, then left I suppose. It could have turned nasty(today definitely) but I wasn’t threatened, but it put the wind up me.

Even in those days Left revisionist propaganda was around . Mine was a small town college, larger institutions must have felt it more.

A concrete example faces the entrance to Home, Manchester’s newish arts venue. An imposing statue of Karl Marx’s friend and benefactor, Friedrich Engels, stands guard here – a Soviet-style monument imported from the Ukraine long after Ukrainian’s had symbolically dumped it when the tyranny of Communism was overthrown. Protests by Manchester’s large Ukrainian community fell on deaf ears. Of course Engels did have Manchester connections but for local arts ‘progressives’ the horrific ‘lived experience’ of a communist ideology he helped to formulate counted for nothing.

Sounds to me like Karl Marx was adopted.

As well as Holocaust survivors speaking on campus to remind British students of the malevolence of the radical right,. . .

A good article except for the all to common misconception that Nazis were Right-Wing.

Communism is International Socialism, Nazis were National Socialists. When Hitler won the election, Stalin sent a telegram to congratulate him.

Hitler’s party was the Socialist Workers of Germany Party.

Socialists are ashamed of WW2 Germany and blame the wrongdoings on the non-existent ‘Far-Right’: Karl Marx’s imaginary enemy – his explanation for why the workers did not revolt. He was convinced that his political theory was perfect, so there had to be something stopping it from coming to fruition – the Far-Right.

Forget the Left versus Right nonsense. Socialism is the cause of all the misery. The rest of us are normal people who refuse to be drawn in to crazy ideologies.

Marxism and communism is distinctive, but more importantly Marxist theory and political and economic regimes that claimed to be communist in the 20th century are also really different. Exploring the links between social theory, politics and the function of power in different regimes could be valuable, however this article adapts sweeping generalisations of Marxism, Communism, social theory, political ideology and the functioning of historic regimes.