The Red Wall is no more, with Labour’s heartlands crumbling as swathes of post-industrial communities across northern England and Wales – Workington, Barrow, Bolsover, Redcar, Sedgefield, Bishop Auckland, Blyth Valley and Wrexham, to name a few – turned blue. Brexit will get done, but in what form? And will the PM be remembered for breaking up the Union?

Despite Jeremy Corbyn’s best efforts to focus the campaign on the allegations that the Tories were going to sell off the NHS in a post-Brexit Free Trade Agreement with the United States, this election was defined by a three-word slogan once again: from “Take Back Control” in June 2016, to “Strong and Stable” in 2017, to “Get Brexit Done” this time round.

Realistically, the Tories should not have returned an 80-seat majority, particularly as they have presided over nine-and-a-half years of austerity. There have been 20,000 police cuts since 2010 and controversial policies such as the Health and Social Care Act and the bedroom tax – yet Corbyn could not land a blow.

Robert Peston alluded to the fact that the result (a 12-point lead) was the same as when the campaign started six weeks ago, so in effect it made little difference.

“Get Brexit Done” was simple and effective, compared to Labour’s strategy of further renegotiation with Brussels and a leader who refused to say whether he backed Remain or Leave.

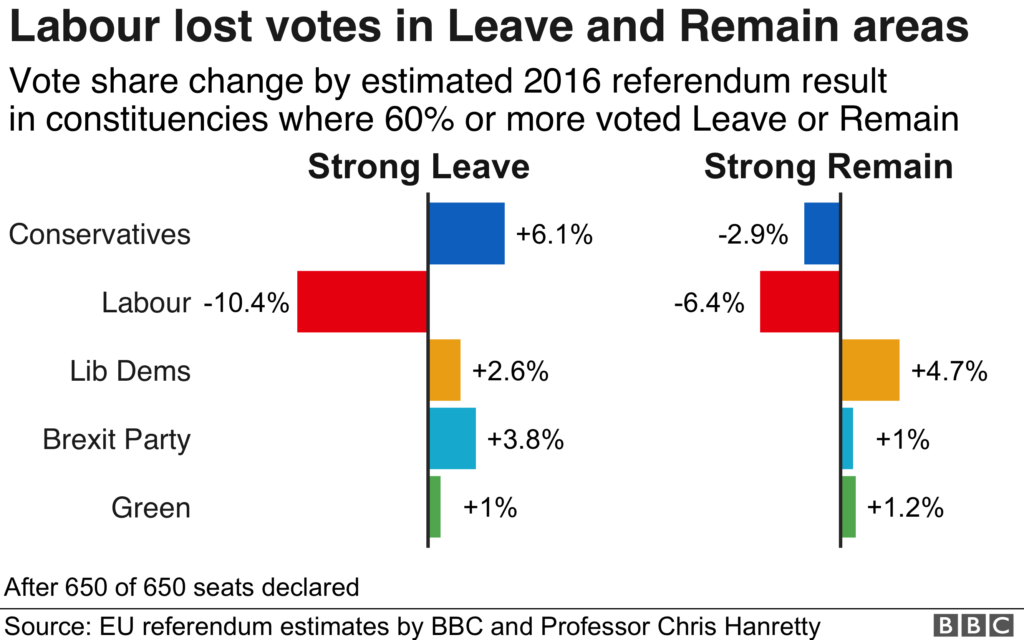

Ultimately, Margaret Thatcher was right. She said that: “Standing in the road is very dangerous; you get knocked down by the traffic on both sides.” Labour suffered a 10.4% decline in Leave seats that voted by more than 60% for Brexit, and a 6.4% decline in strong Remain seats.

Thursday night’s results produced some, quite simply, astonishing and stunning swings of over 18% in Bassetlaw, or 15.5% in Redcar for instance. The gain of seats in Northern England, the Midlands and Wales created an unnatural coalition, where the Conservatives now represent both Cheltenham and Bishop Auckland. Ironically, this was a problem often associated with Labour’s Brexit position, given they had to appeal to Remainers in both Hackney and Wansbeck, where Labour Chair Ian Lavery saw his majority slashed from over 10,000 to 816.

With an 80-seat majority, Boris is no longer dependent on the European Research Group (ERG). Brexit is inevitable; it will happen by January 31st – even Tom Baldwin, Communications Director of the People’s Vote group, and ardent Remainers Lord Heseltine and Lord Adonis, have now accepted this stark reality. That sort of majority could be worrying for the ERG, as it will allow Boris to manipulate Brexit to suit a One Nation Conservative agenda, knowing that he also has to appeal to those constituencies who ‘lent’ their vote to the Tories.

‘Thatcherism on steroids’ – a deregulated Brexit agreement with loose protections on workers’ rights and environmental rights will not suffice. At least, that is, if Johnson wants to retain support in post-industrial former manufacturing communities such as Don Valley and Great Grimsby, which returned Conservative MPs for the first time since 1922 and 1945 respectively. If he doesn’t, then 2019 will be an anomaly and voters will take back their vote quicker than Boris can say “Get Brexit Done”.

It is difficult to see how a comprehensive Free Trade Agreement with the EU can be negotiated in 11 months, given how the Transatlantic Trade Partnership talks failed and the EU–Canada trade partnership took seven years to conclude. However, one way to accelerate discussions would be a level playing field with zero tariffs and quotas, ensuring that manufacturing could be protected. Whilst the ERG could become frustrated quickly, pivoting to a softer Brexit could be a tactical masterstroke, bearing in mind that the communities who voted Conservative did so out of exasperation that Labour had not defended their heartlands.

This election was also dominated by nationalists and the future of the United Kingdom will be, arguably, Johnson’s greatest challenge of the next decade. Brexit was legitimised, but Nicola Sturgeon now has the wind in her sails. Not to mention the nationalists in Northern Ireland, who, for the first time, outnumber unionists.

The SNP holds 48 of Scotland’s 59 parliamentary seats, and she is using her election success as a mandate for a second independence referendum, particularly as she claims the Tories are using the election as a mandate for Brexit in England.

2021 was touted as the year for IndyRef2, to coincide with the Holyrood Scottish parliamentary elections. Now, it will be easy for the Tories to rebuff a Section 30 order – the mechanism needed for the transfer of powers from Westminster to Edinburgh in order to hold the poll. But, as pressure from north of the border grows, it remains to be seen whether Johnson can resist it.

Johnson’s majority is one of historic proportions and caps must surely be doffed; he has triumphed on the European question where Thatcher, Major, Cameron and May failed. However, with a majority of this magnitude, we will find out over the coming months and years just how he intends to shape Britain’s domestic policy into the 2020s, whilst navigating the tricky and choppy waters of Nicola Sturgeon and Scottish independence.