14 May 2021 | ANALYSIS

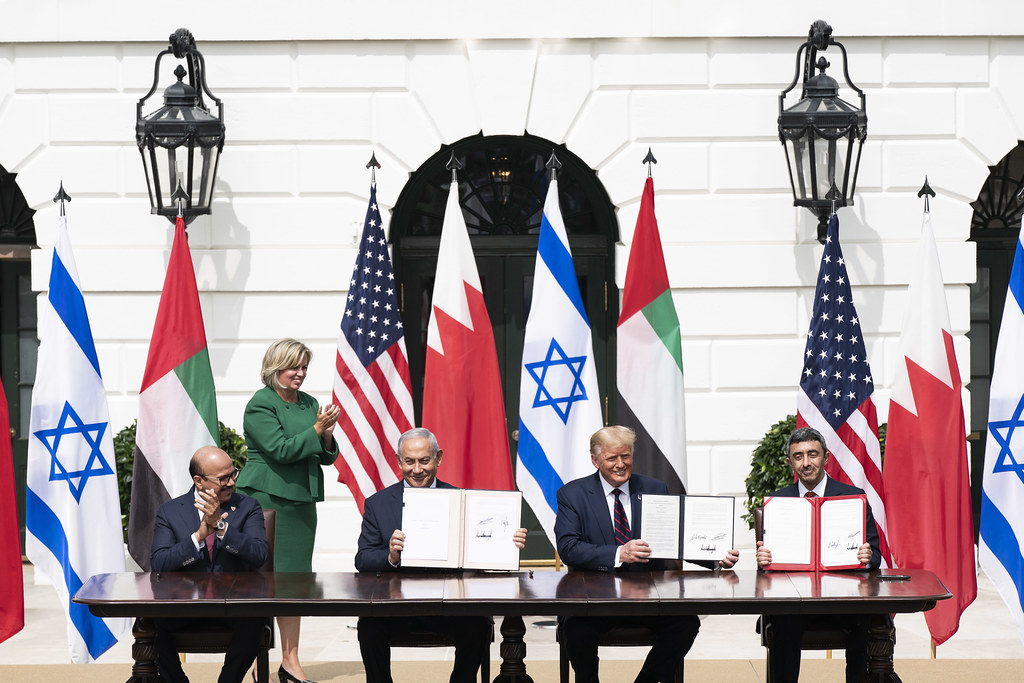

Signed in September 2020, the Abraham Accords are probably the most significant peace agreement in the Middle East in recent history. The agreement was originally signed between Israel and the United Arab Emirates and overseen by President Trump.

However, since the beginning of discussions over the Abraham Accords, several other nations in the region have joined, including Bahrain, Morocco and Sudan. With an increased number of Arab nations signed up to the agreement, concerns over whether it will last can be put to bed. Indeed, the notion that the Accords idea will fail in some way is detached from reality, especially as there are rumblings about more similar peace deals in the works.

Some claim that to some people governed by Arab leaders, their decisions to sign the Abraham Accords could risk resembling a repeat of the conclusion of Anwar Sadat and therefore be regarded with similar hostility. Sadat was the President of Egypt from 1970 – until he was assassinated by Khalid al-Islambouli and others in 1981 – who made peace with Israel in 1979.

However, analogies such as this, and the argument that this will deter Arab leaders now, do not hold much water. The situation is very different from how it was in the early 1980s. Several nations have signed the Accords, meaning that any state actor or terrorist group committing a violent act would find itself in the minority.

The nations that signed the agreement are united in wishing to maintain peace in the Middle East. They have therefore agreed to the wording: “We believe that the best way to address challenges is through cooperation and dialogue and that developing friendly relations among States advances the interests of lasting peace in the Middle East and around the world.”

The Abraham Accords also state that: “In this spirit, we warmly welcome and are encouraged by the progress already made in establishing diplomatic relations between Israel and its neighbours in the region under the principles of the Abraham Accords. We are encouraged by the ongoing efforts to consolidate and expand such friendly relations based on shared interests and a shared commitment to a better future.”

This looks even more likely, as Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has said “there are another four [peace agreements] on the way”. Clearly, there is no impetus in this respect to bring an end to the Accords on the part of any of the nations that signed the agreement.

On top of this, even with a new US President being a Democrat, rather than a Republican like President Trump, who initially oversaw the Abraham Accords, they are unlikely to fail because of a change of heart in the US. Even the alterations made by the Biden administration to the language used in their interactions in the region, such as the renaming of the title of the US Ambassador to Israel to ‘US Ambassador to Israel, the West Bank and Gaza’ was not reflective of a policy change, according to the US Embassy.

Suppose there has not been a policy change, even relating to the US-Israel approach when no other countries are involved directly. In that case, the Biden Administration does not wish to speak negatively regarding the Abraham Accords also signed by several other countries.

As to what the Abraham Accords can offer in the long-term, it could mean an end to the de-escalation of tensions in the region between Israel and many Arab countries. However, unfortunately, most of Israel’s attacks have been from Lebanon, which is highly influenced by the terrorist organisation Hezbollah, and also from Gaza, which is run by another terrorist group: Hamas.

It is doubtful that Lebanon would join the Accords and even more unlikely in the case of Hamas in Gaza. Despite these facts and the complications they signify, the easing of tensions between Israel and many Arab states is a step in the right direction towards a peace in the region that is likely to hold.

Thomas Clowes-Pritchard is a Policy Fellow of The Pinsker Centre, a campus-based think tank which facilitates discussion on global affairs and free speech. The views in this article are the author’s own.