30 May 2021 | ANALYSIS

The dust has now settled on the results from England’s ‘Super Thursday’ local elections on 6 May. Boris Johnson’s Conservative Party emerged as the clear winners. They increased their number of Councillors by 235 and took control of an additional 13 Local Authorities, including Redditch, Cannock Chase and Basildon. But Johnson will also be buoyed by his success in the Hartlepool by-election. His victory, just the sixth by-election gain made by a governing party since the Second World War, has not only exerted pressure onto Sir Keir Starmer’s leadership, but also placed around 20 Labour-Leave constituencies into Conservative sights in the next General Election.

But the Tory gains in the local elections also defied much political precedent. Having been in office since 2010, one would expect the governing party to suffer setbacks across the board. In 1990, for example, Margaret Thatcher’s Conservatives dropped 222 Councillors, lost control in the Tory heartlands of Brentwood, Gosport and West Oxfordshire and were ousted in both the Mid-Staffordshire and Eastbourne by-elections. Similarly, in 2008, eleven years after Tony Blair romped to victory in the Labour Party’s 1997 landslide, Gordon Brown lost 331 Councillors, witnessed London go blue in Johnson’s first bid for the Mayoralty and saw the Conservatives gain an MP in the Crewe and Nantwich by-election.

Subsequently, Professor Rob Ford from the University of Manchester penned a piece in The Observer detailing how the local elections exhibited “the aftershocks of the 2016 referendum”. Given there is now an “inversion” of traditional class-based voting, he also argued that the most significant dividing line in 21st-century political opinion was in education. “In 2021,” Ford claimed, “as in 2019, Labour’s core electorate was graduates, well-off professionals and Remainers”.

Nonetheless, the impact or repercussions of the Brexit referendum has also had a profound impact on the Tory Party’s fortunes. One can see how the Conservatives over-performed in the Brexit-backing Red Wall and many seats that formerly voted for New Labour, before voting to leave the European Union in 2016. In some of their leafy Remain-voting southern seats, including Tunbridge Wells, the party suffered extraordinary setbacks. In the Kent town, a seat that has voted Conservative in every General Election since 1910, the Tories even lost control of the Council. In the neighbouring county of Surrey, the party suffered 14 net losses. However, it still managed to cling on to control of the Council.

The news of the so-called Blue Wall even prompted The Guardian to pay a trip to Chipping Norton, the old stomping ground of the former Tory Prime Minister David Cameron, to investigate the redrawing of Britain’s electoral map. They found that a combination of Brexit, changing demographics and usual protest voting led Labour to gain some True Blue wards from the Tories throughout Oxfordshire.

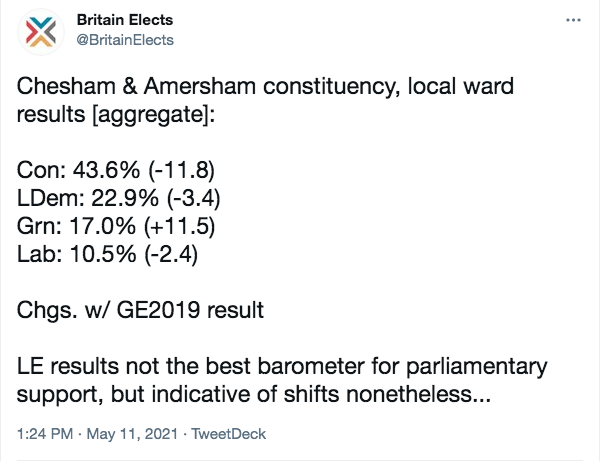

Whilst the Labour Party and the Greens did make some gains in these areas; the Liberal Democrats claim that they are the party to hammer holes into the Tory heartlands. The party’s Deputy Leader and MP for the former Conservative seat of St Albans, Daisy Cooper, said: “From Cheltenham to Cambridgeshire, Wiltshire to Woking, nowhere is safe for the Tories in their Blue Wall.” And now the Liberal Democrat Leader, Sir Ed Davey, is even hopeful that his party can test the Conservatives’ southern retreat in the upcoming Chesham and Amersham by-election.

Researchers at Politics.co.uk estimate that, across the Blue Wall, of which Johnson’s party won 82 out of 87 seats in the 2019 Brexit election, the Conservatives would have suffered six net losses if the result of the local elections were emulated in a national poll. This has prompted dozens of Tory MPs to plead with the Prime Minister to change tack on planning reforms, in fears that this could place a bomb under the Blue Wall. In fact, many Tory-supporting commentators, including Henry Hill from Conservative Home, are now suggesting that a ‘build, build build’ agenda could help reinforce support for the party in its fragile heartlands.

Nevertheless, the evidence that the traditional Tory shires are vulnerable to Labour or the Liberal Democrats is far from conclusive. First, local elections do not necessarily reflect the voting intentions in General Elections. This is not only because third parties, including the Liberal Democrats and Greens, overperform at a local level, but also because resident associations, such as those in Epsom and Ewell, tend to attract voters from across the political spectrum.

Second, local elections are indeed ‘local’ and are often even considered to be protest votes. This means that constituents will not only vote on bins and pavements but also to give a well-needed kick to the Government. Given that some of these areas have also been unapologetically Tory throughout the party’s current stint in power, it should come as no surprise that they might want to remind Number 10, who are increasingly focused on levelling up the Red Wall, that they are still here. Interestingly, one may suggest that this reflects the result in Tunbridge Wells. Whilst the Tories lost control of the District Council, they retained all of their County Council seats in the same area.

So, just how vulnerable is the Tory ‘Blue Wall’?

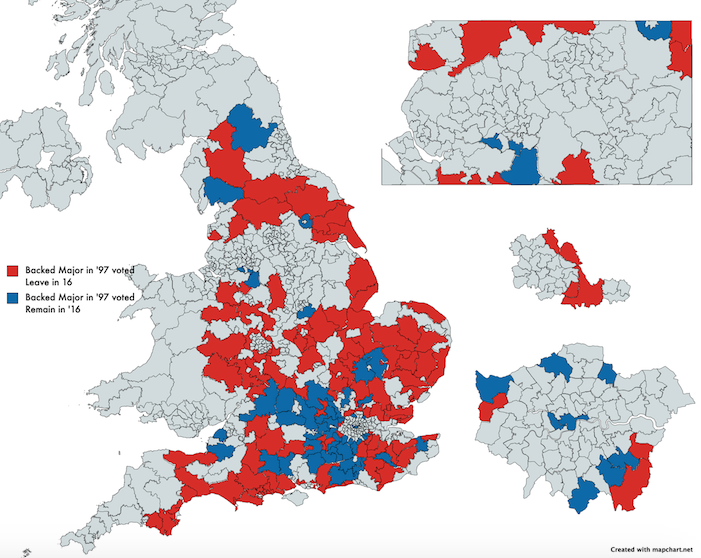

Research by the Wolves of Westminster of constituencies that backed the Tories in Tony Blair’s election landslide in 1997 indicates that how a constituency voted in the Brexit referendum correlates with its recent support for the party.

The 165 seats stretch across England (see below), but around 120 are located beneath the Wash-Severn dividing line. Overall, the Tory heartlands were mostly pro-Brexit, with 115 seats voting leave and just 50 thinking Britain was better off in the European Union. Of those in the south of England but excluding London, 36 voted to Remain, and 84 voted to get Britain out.

It is not easy to directly estimate the results of the local elections in comparison to the 650 constituencies. However, this research has utilised some of the district wards up for grabs, as many of these do broadly mirror the Westminster seats.

Just 29 seats, from Witney to Havant, contested district-level contests on Super Thursday. Across all 29, the Conservatives increased their number of Councillors by an insignificant average of 0.4.

However, a clear difference emerges when comparing seats by their Brexit vote. In the 11 district areas that opted to Remain, the Tories lost on average 1.5 Councillors. In some areas, however, their losses were even more substantial. In Trafford, for example, an area that covers Sir Graham Brady’s constituency of Altrincham and Sale West, the Conservatives suffered four net losses.

In contrast, across the 18 leave-supporting Council areas, Johnson’s party averaged net gains of 1.6 Councillors. But at the Maidstone Borough Council elections, which neighbours Tunbridge Wells and covers the constituency of Maidstone and The Weald, the Conservatives increased their Councillors by 5.

Nevertheless, one can trace this divide by Brexit allegiance in the three most recent General Elections. Across the 165 seats, the overall change in the Tory vote share between David Cameron’s victory in 2015 to Johnson’s in 2019 was around 4.9%. On closer inspection, this was much more profound in Leave-voting seats, which went up by 8.5%, compared to the pro-EU seats, where the party’s vote share fell by 3.5%.

But is this all really because of Brexit?

In short, probably not.

When investigating the long-term shifts in voting, the evidence yet again highlights a much more substantial shift than the change from 2015 to 2019 suggests. In fact, the Leave-Remain gap is equally as prominent. The overall change in the Tory heartland vote between Michael Howard’s 2005 campaign and the 2019 victory stood at 10.5%. Unsurprisingly, the 2005 election is also considered to be the start of the swing towards the Conservatives in the Red Wall.

Nonetheless, in the 50 Conservative constituencies that voted to Remain, the party only increased its vote share by 3%. In many seats, including Hitchin and Harpenden, support for the Tories has even fallen between 2005 and 2019.

In contrast, Conservative candidates in the 115 pro-Brexit heartland seats, possibly aided by the gradual collapse in support for UKIP, saw their vote share rise by a staggering 13.7%. In some seats, such as Aldershot in Hampshire, the number of Tory voters has gone up by more than 15%. Outside of the traditional shire heartlands, this has also seen the Conservatives strengthen their grip on former Labour seats in the south, including Harlow.

If we also accept YouGov’s poll tracker, that suggests that the United Kingdom’s departure from the European Union has fallen from being the most important issue for 75% of voters in September 2019 to the most important issue for just 26% of respondents in May 2021. We could even conclude that Brexit itself is not the cause of this change.

Instead, the differences in voting habits that previously influenced why people voted to Remain or Leave appear to have only been exacerbated and even accelerated since June 23 in 2016.

Therefore, it is increasingly likely that the Conservatives will continue to strengthen their position in Epping Forest, Fareham and Surrey Heath, while also losing support in South Cambridgeshire, Henley and South West Surrey.

But we will have to wait for the Chesham and Amersham by-election on June 17 to see just how vulnerable Johnson’s position in the Conservatives’ pro-EU, and importantly more socially liberal, shire seats really is.

If the Prime Minister’s party can even emulate their success in the Buckinghamshire constituency in three weeks time, then he is sure to be in an exceptionally strong position for the next General Election. But if the Tories are not as successful – even if they only mirror the estimated results from the local elections – then the party will have to be on the defensive in many of their seats, including Dominic Raab’s in Esher and Walton.

In the meantime, however, CCHQ must start thinking about how to bolster support in their Blue Wall. Otherwise, the Conservatives may find themselves in a position in a decade’s time where they, similarly to the Labour Party today, are being punished by a neglected heartland.

In East Surrey, the most conservative part of probably the most conservative county, the Conservative party has just lost control of Tandridge District Council to a residents group alliance

[…] just as Wolves’ recent research on the Tories’ southern ‘Blue Wall’ has demonstrated, support in its pro-Remain seats has wavered in recent […]